By: EWHP 2020 Intern Annie Cebrzynski and EWHP Director Lori Osborne

In 1913, the National American Woman’s Suffrage Association (NAWSA) announced a suffrage “procession” or parade to coincide with the March 4th inauguration of President Woodrow Wilson. The parade would take place the day before and the parade’s purpose, as stated in the official program, was to “march in a spirit of protest against the present political organization of society, from which women are excluded.” The parade was organized by Alice Paul and Lucy Burns, young suffragists just returned from working in the British suffrage movement. Paul and Burns advocated for new tactics and a national strategy in the American movement and in 1912 NAWSA leadership put them in charge of the newly formed Congressional Committee of NAWSA to implement their ideas. The parade was their first attempt at mobilizing American women on a national scale and gaining much needed publicity and exposure for the cause.

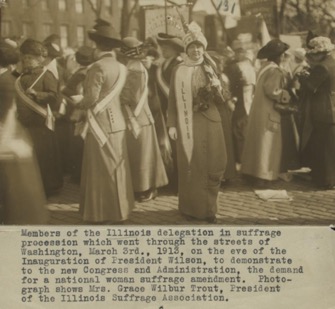

All states that had an established suffrage organization were invited form a delegation to participate in the parade, and the Illinois Equal Suffrage Association (IESA), led by Grace Wilbur Trout from Oak Park, was ready to put a delegation together. Women from all over the state participated, representing their local suffrage organizations. Ida B. Wells represented the Alpha Suffrage Club, which was the first suffrage organization for African American women in Illinois. Formed in January 1913, the club’s first action was to raise money to send Wells to the parade as the only African American delegate from Illinois.

According to the Chicago Tribune, the Illinois delegation of 65 delegates was one of the largest and most prepared state delegations.[i] Before it left Illinois, the delegation practiced and drilled to “march and keep time” and created coordinated banners and uniforms of “cap and baldric” with suffrage and state regalia. The latter were designed by artist Clara Barck (Mrs. George) Welles, Chairman of the parade committee for IESA. Welles was to act as “drum major” for the group, carrying a Civil War era baton. They planned to have one member ride on horseback and, because their lead banner was “too heavy for a woman,” Royal Allen (a railroad official and “ardent suffragist”) was going to march with them and carry it, while Trout herself would carry an American flag. The delegation left Chicago on March 1st on a special train chartered for the purpose.

When the Illinois delegation arrived in the capital late on March 2nd they discovered that there was some confusion about African American women participating in the parade. Though organized primarily by White suffragists, many Black suffragists like Wells planned to participate as members of their state delegations or in one of the many other sections marching in the parade. One section was made up women marching in their professional groups (homemakers, teachers, doctors, lawyers). Another was women’s organizations such as sororities and women’s clubs. In addition, there were 26 floats, 6 marching bands, 6 mounted brigades, and more than 5,000 individual marchers. African American women were dispersed throughout the parade as members of these sections.

Alice Paul had been grappling for some weeks with whether or not the parade would be integrated. Members of her committee warned her that White southern women may not want to march with Black women in an integrated march. NAWSA leaders asked Paul not to make any restrictions on Black women’s participation. Though Paul tried to avoid dealing with the situation, at least partly because she did not want any diversion away from suffrage, eventually the dispute became public. It is unclear how the final decision was made and how widely it was communicated, but at a planning meeting for state delegations, Genevieve Stone, headed this section of marchers, informed the delegation leaders that Black delegates would need to march separately at the end of the parade. (Stone was from Illinois and had joined the Congressional Committee to assist Paul with the parade.)

Each state delegation responded differently to this news. For many it was not a concern as their delegation did not include Black delegates. At a meeting of the Illinois delegation early on March 3rd, Grace Wilbur Trout informed them of what Paul and the parade organizers requested and asked their opinions. A Chicago Tribune reporter was present at this and following meetings, and made note of the sometimes heated and emotional debate that ensued. Some Illinois delegates threatened to not participate if Ida B. Wells was not allowed to march with them. Others felt that Illinois could not go against the request of the national leadership. Geraldine Brooks said “We have come down here to march for equal rights. If the women of other states lack moral courage we should show them that we are not afraid of public opinion.” Wells too spoke up:

“The southern women have tried to evade the question time and again by giving some excuse or other every time it is brought up. If the Illinois women do not take a stand now in this great democratic parade then the colored women are lost.”

Trout at first responded in agreement with Wells, saying “It is time for Illinois to recognize the colored woman as a political equal and you shall march with the delegation.” But after consulting again with the national leaders, Trout returned and told the delegates that Wells would not be able to march with them. Trout noted that she was torn, but had no choice but to do as the parade organizers wished:

“Personally I should like nothing more than to have you represent our Illinois suffrage organization. But I feel we are responsible to the national association and cannot do as we choose. After talking again with Mrs. [Genevieve] Stone, I shall have to ask you to march with the colored delegation.”

In response, Wells declared

“I shall not march at all unless it is under the Illinois banner…Either I go with you or not at all. I am taking not this stand because I personally wish for recognition, I am doing it for the future benefit of my whole race.”[ii]

Both Geraldine Brooks and Belle Squire (co-founders of the Alpha Suffrage Club with Wells) also registered their protest and told Wells they would join her in marching in the separate section. Wells appeared to agree with this and it seemed that a compromise had been reached.

At 2 p.m. the Illinois delegation assembled in its location on New Jersey Avenue and Wells was reportedly nowhere to be found. Brooks and Squire set out to look for her, but returned to the march when they could not find her. What happened next comes down through history as one of the great moments of small protest that mean much more afterwards than they may have meant at the time. Though Wells had appeared to agree to march with the “colored” delegation, instead she joined Brooks and Squire in formation mid-way through the Illinois delegation. The Chicago Tribune captured the famous photograph of the three of them marching together.

The parade itself went well for the first few blocks. Then the crowd of spectators, made up mostly of men in town for the inauguration the next day, began to respond with verbal abuse and even violent confrontations with the nonviolent marchers, breaking through the rope barriers along the sides and filling the streets. The police on hand did little to protect marchers so the marchers and supporters took matters into their own hands, using their mounted participants and vehicles to open the parade route. The parade concluded that night with a rally at Continental Hall.

The poor treatment of the marchers actually made the news coverage even more pervasive than it might have been otherwise, with the parade becoming a national story. When congressional hearings regarding this treatment were held in the weeks following, the coverage of the hearings also gained the movement publicity. Paul, Burns and other NAWSA leaders saw the parade as a big success and it was followed in later years with other large suffrage parades, including two held on Michigan Avenue in Chicago in 1914 and 1916.

But regardless of it serving as a much-needed boost to the suffrage movement, the 1913 parade exposed one of the movement’s primary flaws. In failing to encourage and support the participation of African American women who had worked long and hard for voting rights, the dark cloud of racism that lay over the women’s movement was revealed. Many wonder why the suffrage movement took more than 70 years to reach victory. Certainly, this failure to include all American women in its ranks may be one of the key reasons.

Sources

Primary

“Must March for Suffrage.” Chicago Tribune, Jan 31, 1913.

“Mrs. Welles Assured of Fine Lineup of Illinois Women in Suffrage Parade.” by Marion Walters, Chicago Tribune, Feb 23, 1913;

“Pageant at Washington Biggest Thing Yet Attempted by the Suffragists.” by Marion Walters, Chicago Tribune, March 2,1913.

“Illinois Women Feature Parade.” Chicago Tribune, March 3, 1913.

“Illinois Women Participants in Suffrage Parade: This State was Well Represented in Washington.” Chicago Tribune, March 5, 1913.

“Hoodlums vs. Gentlewomen,” Chicago Tribune, March 5, 1913, p. 6.

“Marches in Parade Despite Protests,” The Chicago Defender, Mar 8, 1913.

“Jeering Mobs are Silenced by Illinois Women in Parade.” Chicago Tribune, Mar 9, 1913.

“Colored Women in Suffrage Parade.” Richmond, VA: Richmond Times-Dispatch, March 2, 1913.

Secondary

Lindsey, Treva B. “Performing and Politicizing “Ladyhood”: Black Washington Women and New Negro Suffrage Activism.” In Colored No More: Reinventing Black Womanhood in Washington, D.C., 86-110. Urbana; Chicago; Springfield: University of Illinois Press, 2017.

Lumsden, Linda J. “Beauty and the Beasts: Significance of Press Coverage of the 1913 National Suffrage Parade.” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 77, no. 3 (September 2000): 593–611.

Wheeler, Adade Mitchell. “Conflict in the Illinois Woman Suffrage Movement of 1913.” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society 76, no. 2 (1983): 95-114.

Jones, Martha –

https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/vote-black-women-200-year-fight-for-vote/

[i] In Sidelights Trout reported that there were 83 delegates but the Chicago Tribune states that there were 65.

[ii] “Illinois Women Feature Parade.” Chicago Tribune, March 3, 1913.

2 thoughts on “The 1913 Suffrage Parade in Washington D.C. – An Illinois Perspective”